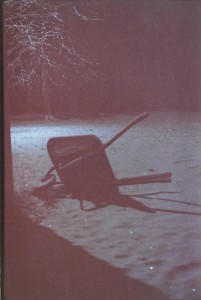

The Red Wheelbarrow

William Carlos Williamsso much depends

upona red wheel

barrowglazed with rain

waterbeside the white

chickens

In 1974, winter hit Fred, Texas, morphing the landscape into an alien world, an ice planet that mocked the wardrobe of the average citizen.

But I was not an average citizen. I had survived the Yankee Exile, served my time at the pleasure of the American Gulag in the land that was high in the middle and round on both ends. I had the wardrobe. And I had a camera.

Actually, it was Dad’s Argus C3, but who was counting?

It had been a year that had rocked the nation. In the heat of summer, Nixon had become the first (and only) president to resign from office. The long national nightmare was over. A month later, Ford pardoned Nixon, prolonging the delirium tremens for the more rabid of his enemies, but as a teenager informed by the satiric stylings of The National Lampoon Radio Hour, I saw the whole melodrama as more of a comic farce.

The sturm und drang of the Passion of the President seemed as relevant to my everyday existence as a lover’s quarrel between the captain of the football team and the head cheerleader. I was as likely to stumble into a fairy tale cast as the knight in shining armor as to peer into the machinery of such exalted proceedings.

With one exception. The lottery held every winter—the day you discovered your odds of being drafted—was controlled by the President.

Like every other America teenage male, I watched the televised proceedings, tracking the likelihood that James Taylor and I would be pressed into service. It was a roller coaster ride. (Although I was pretty sure JT was safe. He had a history that rendered him an unlikely candidate. I, on the other hand, lacked access to the Class A pharmaceuticals that might grant me a similar immunity.)

The first year of the lottery I drew 24, a sure thing for being drafted if I were not four years away from being eligible. Still, it was sobering. The second year I got 254 and breathed a sigh of relief. The third year I got 44. I was still a year away from being eligible, with a whole new drawing a year away to give me a new number, but the threat was becoming more real by the moment.

The next drawing would be for keeps.

Then the unthinkable happened. The next winter, the draft, which had been in place since WWII, was abolished. What else could Nixon do to me? Not much as it turned out. Seven months later he resigned.

By then I was in my first semester of college, enjoying a second level of liberation. There’s a thing thing about being a preacher’s kid. You live in a fishbowl, every aspect of your life under the scrutiny of the general populace. When I went off to college, I left that behind. I was just another citizen.

It’s hard for the average citizen to understand how liberating it is to suddenly find yourself an average citizen. Or how daunting the challenge of redefining yourself. There are so many options. So many potential landmines. And I stepped on a few.

Given my default operating position as an observer and my father’s lifelong interest in photography, it’s not surprising that I found the appeal of a life behind the viewfinder.

I had escaped the horror of war. I had been afforded the luxury of redefining myself. The future was a blank canvas awaiting my first brush strokes. And the uncharacteristic ice storm in Fred, Texas, offered me a spartan palette for the purpose.

I was born during an equally singular ice storm in Fort Worth. Now, eighteen years later, I spied the wheelbarrow abandoned behind the pump house. Somebody, probably me, had left it out.

Countless times I had hauled dirt and sod in that wheelbarrow while helping Dad implement his perpetual mission to leave both the physical and spiritual world better than he found it.

The clean lines of shed and shadow, of wheel and handle against a pristine layer of snow called to me. I donned a coat, grabbed the Argus C3 and light meter, and stepped into the cold.

Evidently Dad had felt the same urge two decades earlier during an ice storm in Fort Worth while attending the seminary.

He obviously had the advantage of years of expertise in technique, but I’ve heard it’s better to be lucky than to be good. I had the advantage of a better subject.

But I can’t help but think that we shared a propensity toward life behind the viewfinder, searching for beauty and purpose in this fallen world.